Privacy Ethics in Home Internet of Things

Overview

- Project Duration: 7 months, on-going

- Year: 2018

- My primary roles: Researcher, Project Management, Study Design

- Tools: Illustrator, Keynote, Google Suite, Remote Testing (Draw.IO; Skype), Microsoft Excel

- Team: Olivia Harold, Eliza Newman-Saul

- Deliverable: Research report, presentation. Capstone to be completed August 2018

Sponsored by Substantial

Current Status

I designed and led a research study consisting of primary and secondary research to investigate the current landscape of home IoT regarding privacy and security. I interviewed and conducted activities with Smart device owners who were concerned about data collection. Research aimed to answer questions about the challenges of protection, current habits, privacy limitations, and knowledge. I generated insights and design principles that will guide the project through the next portion of the project, which will include 3 stages of prototyping and usability testing culminating in a full UI spec document and presentations.

What is the Internet of Things (IoT)?

How might we create a home IoT interface that answers users concerns about privacy and security?

Research Structure: Overview

- 12 participant sessions

- 8 expert interviews

- 30+ literature review papers

- 628 responses to attitudinal survey

Secondary Research

To see what is already known regarding home IoT. Included large-scale attitudinal surveys and publications as professional assessments of the situation. We conducted an ongoing literature review as well as expert interviews.

Literature Review

CONSENT

The current model for consent in IoT is insufficient. We used Batya Friedman's model as a benchmark, and the 6 critical components: Disclosure, Comprehension, Voluntariness, Competence, Agreement, Minimal Distraction (“Informed Consent by Design,” 2005). These components create a foundation for ethical design and are often violated in home IoT situations, for example, the “problem of other peoples things.” This left us wondering what would a truly consensual Internet of Things home environment look like?

VALUE

IoT’s primary value is not in solving a technical challenge, but of improving experiences through convenience, control, customization, and automation. Cisco interviewed 3,000 US and Canadian consumers and found “consumers believe these products and services deliver ‘significant value,” but they don’t understand or trust how the data they share with providers is managed or used.”

PRIVACY AND SECURITY

The largest technical challenge with implementing IoT systems is security. Unfortunately, the “Smart” devices present in homes are particularly susceptible to hacking (Arabo et. al, 2012). Security is further weakened without maintenance such as updating, making systems susceptible to malicious attacks.

DATA COLLECTION

Concerns about the collection of personal data are backed up by quantitative data such as surveys. One survey found that 68% of people were concerned about the exposure of personal data in a connected home environment (Fortinet, 2014). Another found that 85% of Internet users would want to know and control more of the data collected from their devices (TRUSTe, 2014).

Expert Interviews

We conducted interviews on academics and advocates Batya Friedman (Professor at the University of Washington and author of Informed Consent by Design), Gilad Rosner (founder of the Internet of Things Privacy Forum), Michelle Chang (UX Designer at Electronic Frontier Foundation), and Peter Bihr (Co-founder of ThingsCon and Mozilla Trustmark Fellow) (top row), and technical expertise (bottom).

Advocates spoke of the need for transparency, both at the interface level and with data collection. I also gained insight into the players, like government, companies, and individuals, and that the onus of responsibility should not fall on the individual. We also learned about a trustmark currently being developed for IoT products.

WHY I CARE

IoT technology is frontier. The Internet of Things: Interaction Challenges to Meaningful Consent at Scale argues that the emerging field of IoT needs to be embraced by HCI designers who are versed in both technology and human-centered design. It is by this qualification and the responsibility of HCI to “help surface the implications of data sharing in order to develop models of understanding, social expectations for understanding trade-offs, and means for developers to know their designs comply with these expectations and for citizens and policymakers to be able to trust that they do.”

Reported worst-case scenarios further shaped my motivations.

Research Questions

Identified to shape the design of participant sessions and answer qualitative research holes not answered by secondary research.

I wanted to gain insight to help design a product that answers users needs and wants.

How do people evaluate and define privacy risks currently and does it match proven risks?

How do people derive value from connected devices?

What do people understand about data collection from devices and how does it inform their decisions?

What are the complications of protecting digital identity?

When is personal privacy violated?

Primary Research

Recruitment Flyer

WHO

We conducted sessions with 12 subjects (S1-S12; mean=40.5, s=13.57, 4 male, 1 MtF). Targeted participants to get a range of age and gender, as well as the following:

- Potential home-buyers and minimum age of 27 years.

- Own at least one Smart device (baby monitor, thermostat, light bulb, security camera, wireless caregiver, voice assistant, refrigerator, toy, television, plug).

- Self-reported as concerned about privacy and security, but not to the point of paranoid (2, 3, or 4 on the scale of 1 to 5).

WHERE

Participant homes (2; Skype (also from home) (4); Participant workplace (1); MHCI+D studio (5). Interviewing in home when possible preserved some fidelity of self-report.

WHAT

Study activities (conducted on Subject#, changed as saturation was reached)

01. Spectrum card sort (S1-S9)

- Think aloud; sort devices on two spectrums: Value and Risk.

02. Matrix card sort (All)

- Consider Value and Risk concurrently

03. Semi-structured interview (All)

- Measure understanding of connections between devices and security features, privacy protection habits, living situations, and concerns. Questions ordered from low-level to high-level.

04. Privacy policy think aloud (S1-S4)

- Provided voice assistant privacy policy and instructed participants to check if personal recordings are being sent to North Korea.

05. Design activity (S9-S12)

- Draw an ideal device or product to manage these issues. Instructions were left vague, and creativity encouraged.

Spectrum card sort

Synthesis

We coded attitudinal verbalizations from each audio and video session.

Because of the large quantity of data we collected, I decided to exclude behavioral information. It will be referred to in the design stage.

Mental Models

Perceptions of Data Collection

Perceived Value and Risk of Smart Devices

I used each card sort artifact to sort devices by participant as Low, Medium, and High in Excel. I aggregated the ratings and created the following charts which highlighted interesting differences between value and risk judgements.

Value

Participants assigned their own definitions of value, which differed both according to person, and even across devices within the same participant: convenience, financial savings, environmental monitoring, home automation, entertainment, comfort, home modification, health monitoring, connection management, and accessibility.

Routers ranked highly because of their essential nature: they make the functionality of every other connected device possible. However, they are seen as mandatory infrastructure.

Wireless caregivers ranked highly because of the freedom and accessibility. Human-centered questions were raised when one participant described how much everyone in her family loved her mother’s wireless caregiver, except for her mother, who would often show her disdain by removing the battery.

Voice assistants were valued for entertainment and convenience.

Smart thermostats, like Nest, were “loved” by participants that owned them, and desired by most who did not. Comfort, environmental and financial economy, and interface design were cited as advantages.

Smart refrigerator and baby monitor ranked lowly because of gratuitous “smartness” and potential spying.

Risk

Participants assigned their own definitions of risk. Definitions differed both according to person, and even across devices within the same participant: spying potential, reliance, reliability, multiple entities having access, device always on and the brands security reputation.

The lowest ranked risks are simple devices like Smart plugs, Smart light bulbs, remote control, and connected speakers. These devices are seen as less systemic and therefore hacks would sacrifice less personal information.

The diversity of risk assessment is highlighted in voice assistants and security cameras, which are tied for highest risk. Voice assistants have high potential for spying, whereas the fears about security cameras are societal (they perpetuate paranoia and inequalities).

Concerns: Survey Results

Instead, I combed through the data and sorted responses into broad fitting categories.

Users had the chance to explain their answers. In this population that is heavily biased towards home connected devices, the majority still expressed concerns about privacy and data collection.

The survey was meant to play a supplemental role to attitudes we explored with participant sessions. Most responses were after posting to reddit.com/r/homeautomation and reddit.com/r/googlehome. I used Google Forms to collect responses, and exported to CSV for analysis. I outsourced the data for statistical analysis, but ultimately decided that the questions were not controlled enough to draw convincing conclusions to explain significance.

Sometimes responses consisted of a range of explanations:

“(I’m uncomfortable with data collection) if (the devices) use Facebook or LinkedIn.”

“Alexa freaks me out sometimes. Don't necessarily care about things like moisture sensors collecting usage info.”

17% of Yes answers included a conditional (e.g.: Devices are secure if you know how to use them properly). Not with cloud connectivity: anything connected to the cloud is not secure. There were instances of users who set up entire offline home automation networks to avoid the cloud.

Abstracting to Personas

I sorted each subject into two spectrums based on themes that arose during the interview phase: amount of technical command, and amount of concern. The hashed area contains our users we will design for. Some users were omitted because their concern was so high that they avoided connected devices, or because their technical expertise made them self-sufficient at protecting their privacy.

I identified themes from user interviews and abstracted to craft 4 personas: 2 target users and their anti-personas. I designed anti-personas because knowing why people are untroubled also informs our design, but convincing users to be concerned is outside the scope of our design solution.

Primary Personas

(Click to enlarge)

Negative Personas

Addressing Assumptions

Insights

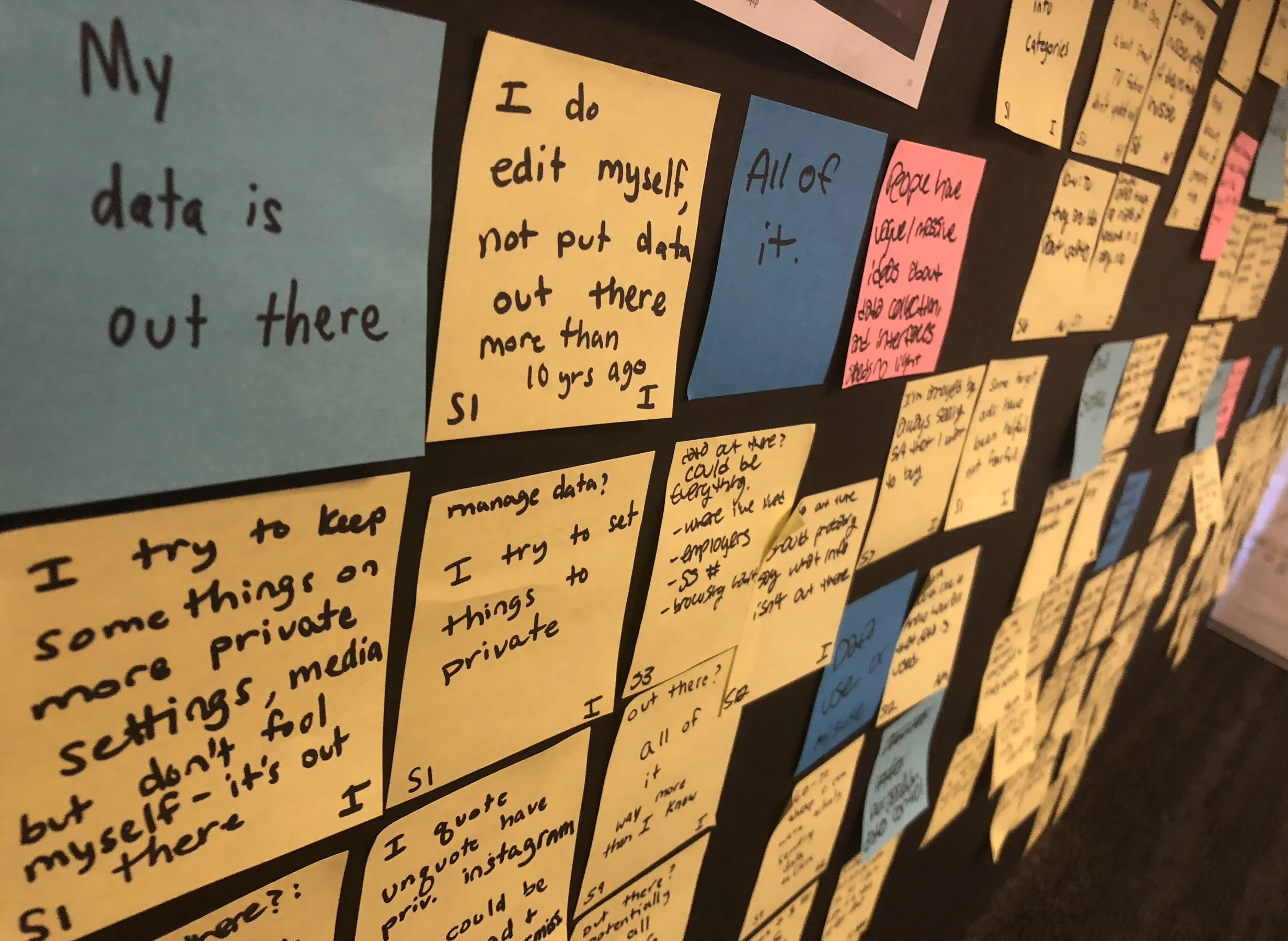

01. PEOPLE HAVE VAGUE AND MASSIVE IDEAS ABOUT DATA COLLECTION.

“I try to keep some things on more private settings, but I don’t fool myself, it’s out there.” (P1)

“Data being out there is a reality of modern America.” (P9)

Participants struggled to describe what specific data about them is out there, and most simply said “everything.” They also believe that data is never deleted, and every part of their digital identity remains outside their control. Some people spoke about specific hacks that had affected them. Although they knew what information had been leaked, they concluded that now everything was compromised. It was impossible for them to get a clear picture because they were never sure of the extent of the hack.

02. SOCIAL AND NEWS EVENTS MAKE TECHNOLOGY UNDERSTANDABLE AND MOTIVATE PEOPLE TO CHANGE BEHAVIORS.

“Turns out Alexa is storing audio info...my jaw dropped, wait what?” (P2)

“I subscribed to a VPN, but sometimes I forget to pay and it runs out, then something happens that reminds me of why I wanted it in the first place.” (P3)

We saw that many people took action and changed behavior after a news event, or after conversations with friends. This indicates that people are looking for outside sources of information. We hypothesize that part of the explanation is that mainstream media, as well as peers, explain complicated concepts in understandable terms rather than technical language. Almost every participant had heard about the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal and had an opinion. These social events often serve as a motivator for taking action to protect their privacy, such as deleting Facebook or checking their records.

03. INDIVIDUALS PERCEIVE PRIVACY MANAGEMENT AND MAINTENANCE AS CONFUSING AND TIME-CONSUMING.

“I don’t have time to maintain or update... It shouldn’t be on the individual to be constantly defending themselves.” (P3)

“Companies provide the tools and information, but what user controls anything with that level of granularity?” (SME)

The Troubled Casual technology users expressed a desire to understand. Even if information about privacy management is easy to access, people see it as time- consuming and often do not maintain privacy habits. One person came to us because she was concerned after reading her Alexa voice logs on Amazon. She mentioned that accessing the records was easier than she expected. For the privacy policy reading task, participants usually could understand and piece together the information. They often recognized when the language was purposefully vague. However, they became bored very quickly. A boring task, although easy, will contribute to a higher perceived workload and lower sustainability of a behavior.

04. WE LIVE WITH BEING HARVESTED FOR THE BENEFIT OF CONNECTION AND CONVENIENCE.

“I had to sign a bunch of agreements that I wasn’t fond of.” (P8)

“We give up privacy for convenience, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be cautious.” (P2)

Data collection is troubling but not enough to give up services and benefits. For example, the social connection provided by Smart phones, or convenient way-finding provided by location-tracking. An avid runner said that the biometric data he was receiving from his Garmin watch was more useful to him than his data was to Garmin.

05. IOT TRENDS TOWARDS OPAQUE INTERFACES.

“I applaud people who go to extremes to research devices and what they can do.” (P9)

“As I become more informed I become more suspicious.” (P2)

Devices are geared towards completing tasks and minimum interactivity, and are not informative about themselves. There is a mismatch between the need for easy troubleshooting and building trust with users through transparency, and opaque design trends.

06. CONCERNS ARE LARGELY ON A SOCIETAL LEVEL RATHER THAN AN INDIVIDUAL LEVEL.

“Metadata like the time I sent a text seems harmless, but at a societal level it’s creepy as hell.” (P6)

“Data harvesting can swing elections and encode inequalities in society.” (P8)

People justified their inaction by saying they don’t feel like targets. They described themselves as law-abiding citizens, and stated that they would be more concerned if they were in a different situation, like being a reporter in Russia. Furthermore, their data is thrown into an aggregate. However, 11/12 participants stated that they were very worried about the effects of data collection on society at large.

Design Principles

01. Lower the mental load.

02. Prioritize convenience.

03. Make interfaces transparent and understandable.

04. Think long-term.

05. Avoid fear-based solutions.

Impact

Participants taking action:

We received a follow-up message from a participant a couple days after his interview session. This person had a range of connected home devices, and was already especially involved in informing himself about data collection.

“After chatting yesterday I’ve been thinking more and am going to build my own DNS next week so I can control and monitor traffic at the network level and block ads at the DNS request level... I’m excited about it, gonna set it up with a ton of blocklists, picked up a 3.5” touchscreen so it’ll have a constant monitor/visualization of blocking stats.”

And starting to think more:

Another participant mentioned that our line of questioning and made her reflect on some of her privacy practices and alter her behavior. Through these interviews it became clear to us that users want to discuss and reflect on their privacy maintenance behaviors. Many wondered ‘should I do more’? A small amount of conversation can motivate people to be more aware of their data and lead them to practices that more directly meet their goals.

Future Directions

We will begin the design phase by ideating 70 concepts . We will down-select based on feasibility, desirability, and viability, using our previous research to determine each. The final 3 concepts will be prototyped and usability tested on potential end users.